What does Sequential Learning mean?

As an expert on the topic of the course(s) you want to teach, you have a comprehensive 360-degree view of your course material. You’ve spent many years, maybe a lifetime, mastering your subject matter. And now you want to share your expertise with your chosen target audience. You want to provide lots of value, so it would be great to share everything you know. That you’ve learned in a lifetime. All at once.

Here’s the problem with that: due to the very tight limits of working memory (the part of the mind we use to process and store information), people can only take in, absorb, and process a small amount of information at a time.

An expert on a topic didn’t acquire their 360-degree view of the material all at once, and learners can’t either. The only way to take in, process, and learn information is one (SMALL) step at a time, in a sequential manner.

A helpful metaphor for understanding how we can take in and process large amounts of information, step by step, is to think of a mosaic. Mosaics can be very large… they often cover the entire floor, walls, or ceiling of a building. But each tile in the mosaic is tiny. Put the tiny tiles together in the right order and they create a beautiful, comprehensive picture… but it’s a picture that has to be built up one small step at a time.

Why is the sequencing of learning so important?

Continuing the mosaic metaphor, you might ask: why can’t the small pieces of our (mental) mosaics be laid down randomly, in any order we want? Why do we have to learn each small piece in a specifically sequential order, in addition to learning one step at a time?

The reason for that is that the steps in a learning sequence build on each other. Complex skills (like mastering artisanal baking) depend on the prior learning of simpler skills (like properly combining wet and dry ingredients, or performing smooth wrist motions for beating air into batter).

In order to effectively use the higher-order thinking skills described in Bloom’s taxonomy (skills such as analyzing, evaluating, and creating something new), learners must first master lower order thinking skills relating to the same material (such as remembering, understanding, and being able to apply what’s being taught).

If you’ve ever experienced what it’s like to be shown how to do something once, by an expert, and then asked to perform that same skill or activity yourself, right away, you know the “deer in the headlights” feeling that being asked to perform a skill without enough preparation and guidance, can cause.

Gagné’s nine events of instruction can be used for effective lesson planning. Both logic and experience show that it’s not effective to go directly from presenting the instruction (event 4) to expecting independent performance (event 6). Event 5 (guided practice) is missing in that learning sequence, and guided practice is needed to help learners succeed in performing on their own.

Related: The Ultimate List of Free Online Course Lesson Plan Templates

Another factor to consider is cognitive load, which describes the difficulty involved in learning something new. The inherent difficulty (intrinsic cognitive load) of a specific learning task is relative to the learner’s prior knowledge. If a learner has been studying organic chemistry for years, taking a new step into a specific area of related research will not be a big leap for them. But for someone who’s never studied chemistry at all, that same new research step would be far too difficult for them to perform.

Gagné defines teaching as arranging a series of events that promote learning[1]. We can understand these “events” as referring to the 9 events of instruction within ONE lesson, and also as referring to the sequence of lessons within a course, the sequence of courses within a bundle, or the sequence of bundles within an academy.

Online learning has to be designed

The closer an online course is to being “evergreen”, the more carefully it has to be designed in order to produce real learning. That’s because to the extent the instructor is not actually present in real-time (either in person or live online), the course ITSELF has to stand in for the instructor by anticipating and responding to the learner’s needs.

Instructional design involves anticipating and planning for the needs of learners as they move through a learning experience step by step. Sequencing the learning properly provides a smooth, incrementally progressive learning journey where each small step allows the learner to be successful in a continuous way.

Learners experience a feeling of self-efficacy (being able to take effective action on their own behalf) and achievement, when each part of the learning journey builds on the previous step and prepares for the next one. Gagné identified self-efficacy and achievement as important motivational factors that keep learners moving forward and engaged in the learning process.[2]

Experts often try to fit everything they know into a single online course, only to realize that it’s too much information for learners to absorb at once.

More important, there are pre-requisite skills learners need to master, before they can achieve the learning goal (“Point B”) for a whole course or program.

Learners MAY need to have certain skills, behaviors, and attitudes in place before they are even ready to ENTER your course or program (at “Point A”, the starting point of your course).

Instructional designers use a process called a task analysis to break learning down into target learning objectives and then determine the pre-requisite learning objectives needed to achieve the target learning goal. There are two types of pre-requisite learning objectives:

- Enabling objectives (which are essential to ENABLE learners to eventually achieve the target objective)

- Supportive objectives (which are helpful and nice to have, but not 100 percent required for the learner to eventually achieve the target objective).[3]

If you are teaching someone how to decorate a cake, an enabling objective would be ”learn how to bake or otherwise obtain a cake”. That objective is essential because course participants can’t decorate a cake if they don’t have one to work with.

A supportive objective would be, “Learn how to mix your own cake icing colors”. That objective is supportive because being able to mix their own colors would greatly enhance the decorating experience. But it’s not essential because learners will also be able to successfully achieve the target objective of learning how to decorate a cake using pre-mixed icing colors.

The process of sequencing learning objectives can get technically complex and requires a high level of learning design skill. If you’d like to read about it in detail, the following sources go into depth:

| Principles of Instructional Design (2005): |

|

| Essentials of Learning for Instruction (1988) |

|

| Course Design Formula: How to Teach Anything to Anyone Online (2019) |

|

Related: How to Use Backwards Design To Create Your Lesson Plan (Template + Steps)

So how can you get great results in your online course, without going to school to get a degree in instructional design?

How do you decide the scope, scale, and sequence of what you want to teach?

Let’s look at what many course creators go through, and then reverse-engineer the process to streamline and simplify the way YOU determine the pre-requisite skills your course participants will need at every level of your online program.

Here’s what many course creators go through:

They sit down to plan out a course to teach people how to perform a skill.

As they start writing down the steps involved in performing the skill, they have an “aha” moment:

they realize that before course participants can even begin performing the skill, they’ll have to improve their mindset about doing it. Otherwise, they won’t even try.

There are so many problems that could stop learners from even trying to perform the skill. Which mindset problem do they even HAVE? Do YOU know? Do THEY know? How can you find out?

One idea is to put a quiz on your website that helps people figure out what their worst problem or pain point is that is getting in the way of performing the skill. That way, you could send them follow up emails or create a special group for them (or even a pre-requisite course), to help them get into the right mindset needed to perform the skill.

And THEN you can start teaching them the skill.

So it turns out that before you can even START to teach anything to anyone, you have to understand the entire SEQUENCE of learning needed to get from where your course participants are starting from, to where they want to end up.

Your course is the way learners will get from Point A to Point B. So the first step is to define what point A is for them.

But wait…what do we mean by “THEM”? Who is your target audience for the course you’re creating? What relevant prior knowledge do they already have about the topic, and what (if anything) are you going to have to teach them before they are ready for the main topics you want them to learn?

But wait…what do we mean by “THEM”? Who is your target audience for the course you’re creating? What relevant prior knowledge do they already have about the topic, and what (if anything) are you going to have to teach them before they are ready for the main topics you want them to learn?

It turns out that there are a lot of pre-requisite skills that you, as a course creator, need to use, before you start actually planning your course. These pre-requisite skills include:

- Having a well-defined learning goal for your course as a whole (Point B, your student’s desired future)

- Having a well-defined starting point for your course (Point A, your student’s current reality today)

- Understanding who your target audience is

- Understanding what your target audience already knows (what skills and behaviors they already have) relative to what you’re about to teach them

And that’s all before you even begin creating your course. It can feel overwhelming, but having a clear plan of action can help you create a learning sequence you can use to design not only any specific course, but your entire online school.

One of the first big ideas to understand (and sometimes this only becomes clear after you’ve thought through what you want to teach, for a while), is:

What is the SCALE of the learning you are trying to design?

Interestingly, getting clear on the scale of what you are building helps the pre-requisite steps needed at every level of your program, fall into place. So let’s explore this issue of scale, and how it can help you set up your program on Thinkific both quickly and easily.

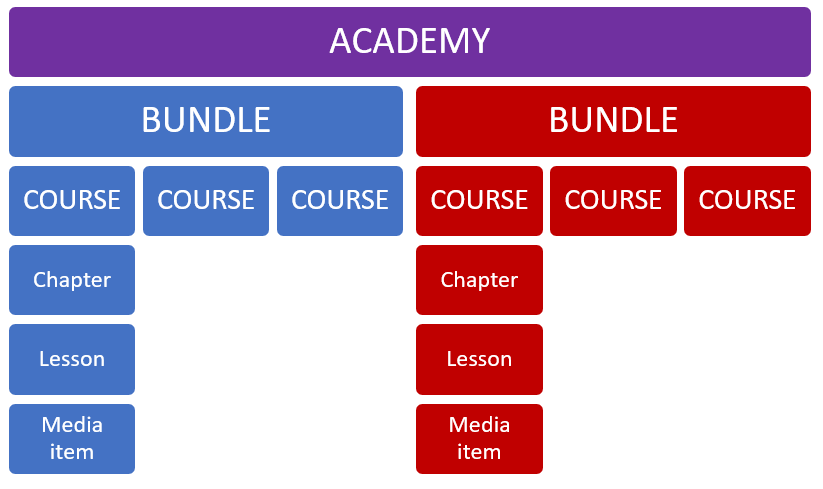

Your whole online academy or school

At the largest scale, you could be trying to create a whole online ACADEMY, unified around a single learning goal. Examples of an academy learning goal would be:

- Become a master of the culinary arts

- Build great relationships with your children as they grow

- Enhance your study skills for graduate school

As you can see, these are LARGE, comprehensive learning goals. Each of them requires multiple smaller learning goals that course participants need to master before they can achieve the overall comprehensive learning goal. Fittingly, Gagné and Merrill (2005) refer to this type of large comprehensive goal as an “enterprise”.[4]

Many course creators start out thinking they can teach all the skills needed to achieve their top-level learning goal (their entire enterprise), all in one course. This soon starts to feel overwhelming to the course creator, and far more so to any potential students.

Instead of a single course, breaking down the top-level learning goal into multiple pre-requisite learning goals makes this a much more do-able exercise.

Each smaller learning goal becomes the “Point B” of its own complete course. You can set up an academy on Thinkific as an entire Thinkific school or membership site, containing multiple courses.

Bundles of courses within your school

The next level down in scale is the Bundle level.

Let’s see how this works for “Become a master of the culinary arts”.

Working backwards using a process of backward design, if we analyze the “enterprise level” learning goal of “becoming a master of the culinary arts” we can see that there are several questions we need to ask ourselves:

- What are the culinary arts?

- What does it take to master them?

- (Let’s say you determine that it requires becoming both a master baker and a master chef).

- What skills does a master baker need?

- What skills does a master chef need?

- Do baking skills and chef skills build on each other, or are these two parallel tracks?

- What other skills would someone already have to have in order to develop master baking/chef skills?

- How can learners obtain those earlier skills?

- Do you want to teach the earlier skills, or set them as pre-requisites that someone entering your online program must already have?

- If you want to teach the skills, how will you do that?

Let’s say that you want to teach the skills yourself, and you determine that the pre-requisite skills for becoming a master baker are:

- Learn how to source ingredients

- Learn artisanal baking techniques

- Learn artistic decorating secrets

Each of those skills can become the learning goal for its own course.

Courses within bundles within your school

As you start working on the ingredients course, you realize that there’s a lot to it. You are going to have to help your course participants understand supply chains, sustainable farming, weather patterns, pricing issues, customer food sensitivities, and many other issues.

Each of those topics could become a whole course in itself… in which case you could turn “How to source ingredients” into a bundle of courses on Thinkific. Or each of those skills could become the learning goal for a specific CHAPTER inside one integrated course.

The scale you are going to use is a design decision that you as an instructor will need to make.

Let’s say you go for the CHAPTER option, because while sourcing ingredients is important, it’s not your main focus: baking is… and you want to get to that as soon as possible.

Thinkific offers you a lot of flexibility in how to structure your program, depending on the learning design decisions you make. Let’s say that you decide you just want your learners to take ONE course about sourcing ingredients, rather than go super granular on that topic by creating a whole bundle of courses (which would take your learners more time to go through).

Chapters within courses within bundles within your school

The CHAPTER level

So you’re going to create ONE course about how to source ingredients for masterful baking, and within that course you will have a chapter about sourcing ingredients based on customer food sensitivities.

Continuing to work backwards, you’d be thinking about what your course participants need to understand about the current landscape of customer food sensitivities and how that affects ingredient sourcing for master baking. Within that chapter you might have a LESSON on gluten- free baking products and where to source them, a lesson on bulk sourcing for alternative flours, a lesson on seasonal availability of alternative products, and so on.

Lessons within chapters within courses within bundles within your school

The LESSON LEVEL

Within each lesson you will have one or more MEDIA ITEMS.

Media items are the most granular level of digital media for online courses. If we were building with Legos, media items would be the individual Lego blocks.

A single video, PDF, or Word doc is a media item. A lesson might consist of just ONE media item, or might have more than one.

In terms of sequencing the learning in your course, it’s important to always start from the level above what you’re creating and ask what learners must be able to do to get there.

So if the lesson’s learning goal is “understand bulk sourcing for alternative flours”, you might need a guide to the different types of alternative flours (which might be a PDF for example), a video explanation of the best bulk sourcing practices, and a directory of bulk sourcing providers for alternative flours. So that one lesson would contain three media items.

Media items within lessons within chapters within courses within bundles within your school

The MEDIA ITEM LEVEL

There are several important concepts to keep in mind with respect to media items. One is the idea of making them RE-USABLE. For example, if you create a video about bulk sourcing best practices, and later create your master chef program in addition to your master baking program, you might be able to re-use the same video as long as it explains bulk sourcing practices in a way that applies to both baking and cooking in general. The Thinkific video library makes it fast and easy to upload and store videos in ways that allow you to re-use them in multiple courses.

Another important idea relating to media items is the importance of making them accessible, so that everyone can use them. Adding close captions to videos makes your videos accessible for those who are not able to hear, and also enhances the usability of your videos for those who are non-native speakers or who are watching the video in an environment where audio needs to be kept off. The Thinkific video library makes it fast and easy to upload captions to your videos.

Using learning sequences to set up your entire online school

Let’s recap:

If the goal of your entire academy is to teach people to master the culinary arts, you might have:

- A bundle of courses on how to become a master baker

- a course on how to source baking ingredients

- a chapter about how to source baking ingredients for alternative food preferences,

- a video about bulk sourcing practices

- A bundle of courses on how to become a master chef

- a course on how to source cooking ingredients

- a chapter about how to source cooking ingredients for alternative food preferences,

- a video about bulk sourcing practices

- a chapter about how to source cooking ingredients for alternative food preferences,

- a chapter about how to source baking ingredients for alternative food preferences,

The great thing is, you don’t have to reinvent the wheel. Thinkific makes it fast and easy for you to:

- re-use videos from your video library in multiple lessons and courses

- copy lessons from one course to another

- copy courses

- copy bundles

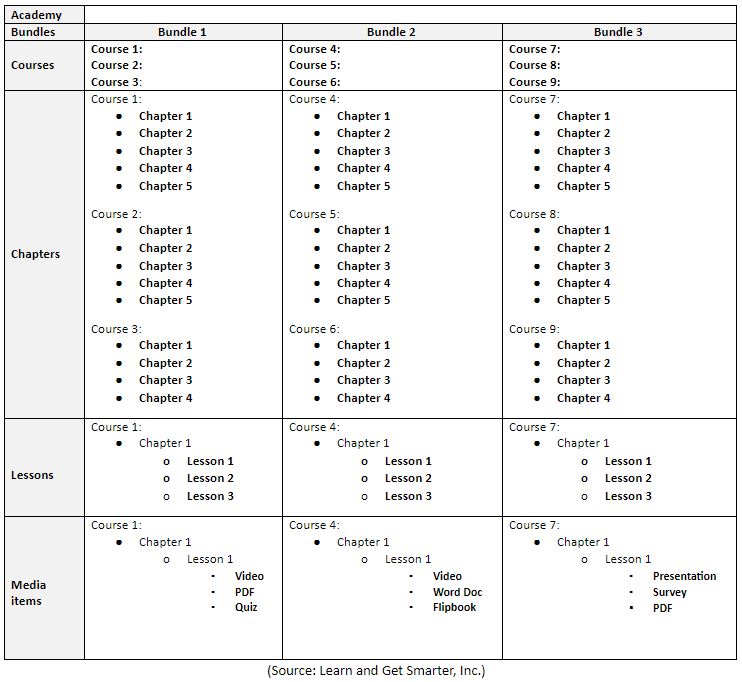

We’ve created a handy chart you can use to map out your entire academy.

First, think about the learning sequence you want to build into each level of your online program.

- ACADEMY LEVEL: The overall, highest level, learning goal of your entire enterprise

- BUNDLES: The major learning tracks/paths you want to provide

- COURSES: Specific attitudes, behaviors, strategies, skills being taught within each learning track

- CHAPTERS: Large chunks covering major topics within each course

- LESSONS: Small chunks covering a specific aspect of each major topic

- MEDIA ITEMS: Granular media artifacts within each lesson that provide the actual instruction

Learning sequence examples and template

Imaginary Academy: Masterful School Of Culinary Arts

| BUNDLE: MASTER BAKING PROGRAM | BUNDLE: MASTER CHEF PROGRAM |

| Course: How to source ingredients for baking Chapter: Sourcing alternative baking ingredients Media item: bulk sourcing practices video | Course: How to source ingredients for cooking Chapter: Sourcing alternative cooking ingredients Media item: bulk sourcing practices video |

| Course: Artisanal baking techniques | Course: Top tier cooking techniques |

| Course: Artistic decorating secrets | Course: Secrets of sauces and garnishes |

Then, use a chart like the one below to plan the learning sequence for your whole academy. Use the template for yourself!

If you understand the scale of what you’re creating, and follow a process of backward design from the most comprehensive skill to the most granular, you’ll be using the structural features built into Thinkific to perform an on-the-spot task analysis of your own.

As you work backwards from your highest level learning goal, ask yourself: What smaller skills must learners master in order to be ready to learn this?

Keep going all the way down from the most comprehensive whole academy level to the most granular media item level.

After you design and plan your program backwards, you can then build it forwards… starting to create digital media from the most granular media items such as individual videos, and working your way up to lessons, courses, and bundles as you create your online school. This way of working will ensure a smooth, well-designed learning journey for your course participants, and an efficient course creation process for you.

Summary and Recap

Let’s return to our mosaic metaphor for a moment: in designing the sequence of instruction for your online program, start by standing back to get the big picture view of the whole mosaic. What is the overall learning goal you want your program participants to achieve?

Then break that large enterprise learning goal down into smaller component parts, getting more and more granular as you work backwards from the level of bundles or tracks within your overall program, to individual courses within bundles.

For each course, start with the learning goal for the course as a whole. Then use a learning design process (such as the Course Design Formula®, which helps you structure your course and lessons using research-based best practices) to structure the chapters within your course, the lessons within your chapters, and the media items within each lesson.

Taking this enterprise/academy-wide view will enable you to see where some of your media items can be re-used for various courses, which will simplify and streamline your work once it comes to actually creating your digital media. Most importantly, you’ll see how every part of your online program can work smoothly with all the other parts to ensure a clear, effective, and engaging learning journey for your course participants, helping them reach the learning goals you set for them, each step of the way.

Sources

[1] Gagné & Driscoll, 1988, p.v.

[2] Gagné & Driscoll, 1988, pp.64-66.

[3] Gagné, Wager, Golas, & Keller, 2005, p. 151

[4]Gagné, R.M., Merrill, M.D. Integrative goals for instructional design. ETR&D 38, 23–30 (1990).

Gagné, Wager, Golas, & Keller, 2005, p. 151.